Prejudiciële vragen: Zijn onbevruchte menselijke eicellen een menselijke embryo?

UK High Court of Justice, 17 April 2013, [2013] EWHC 807 (Ch), (International Stem Cell Corporation v Comptroller General of Patents)

Octrooirecht. Biotechnologische uitvinding. Er wordt voortgebouwd op de Brüstle-vragen/beslissing [LS&R 403]. The question to be referred: The parties have suggested that the following question should be referred. In my judgment this succinctly identifies the issue. Subject to any further submissions, this is the question that I intend to refer:

Octrooirecht. Biotechnologische uitvinding. Er wordt voortgebouwd op de Brüstle-vragen/beslissing [LS&R 403]. The question to be referred: The parties have suggested that the following question should be referred. In my judgment this succinctly identifies the issue. Subject to any further submissions, this is the question that I intend to refer:

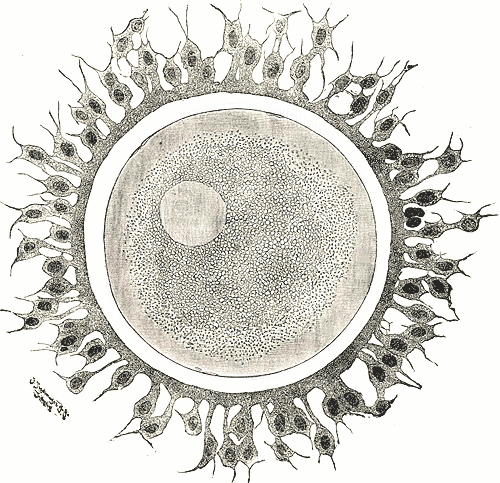

Are unfertilised human ova whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis, and which, in contrast to fertilised ova, contain only pluripotent cells and are incapable of developing into human beings, included in the term "human embryos" in Article 6(2)(c) of Directive 98/44/EC on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions?

48. As to the referring Judgment, the Comptroller points out that the citation from [44] relied on by ISCC is incomplete. Once one takes into account the remainder of this paragraph, it is much more difficult to suggest that the conclusion of the CJEU expressly contradicted the findings of the Bundesgerichtshof. In particular, the German Court went on to say:

"Independent of this one point in favour of qualification as an embryo as defined in Art. 6 para 2c) of the Directive could be the fact that such cells in any event in the first division stages go through the same development as a fertilized egg cell and therefore appear equally worthy of protection."

My understanding of this passage is that the Bundesgerichtshof was pointing to the similarity between initial stages of development of parthenotes and fertilised egg cells and hypothesising that it could be said that parthenotes were equally worthy of protection from patentability.

49. The Comptroller further submits, correctly in my view, that whilst the Advocate General was clear that the dividing line was whether the cells were totipotent or pluripotent, it does not appear that the CJEU followed this distinction. Unlike the Advocate General, the Court did not frame its decision in relation to parthenotes on a conditional basis, even though it clearly had in mind the distinction between pluripotent and totipotent cells (see paragraph [22] of the CJEU Judgment).

50. Therefore, the Comptroller submits that it is unclear whether the test that the CJEU had in mind turned on merely commencing the process of development of a human being (whether or not the potential exists for the completion of the process), or commencing a process which is capable of leading to the birth of a viable human being. For the reasons given by Mr Mitcheson on behalf of the Comptroller, I agree.